|

Bereavement is what happens to you; grief is what you feel; mourning is what you do. Dr Richard Wilson The Whirlpool of Grief model was created by Dr Richard Wilson, who worked with parents who had lost a child. The idea behind the Whirlpool of Grief is that we are pottering along the River of Life, when we are swept down the Waterfall of Bereavement. It feels like we have been swept off a cliff, and we are hurtling down, out of control, numb, in shock and perhaps in denial.

We land in a whirlpool of grief, where we feel lost, emotionally disorganised and falling apart, and as we get swept round, we might go through the same things again and again. We might get battered on the rocks, where we feel the physical symptoms of grief. We might get washed into shallow water where we can rest, or onto the banks, where we experience the fog of widow brain, and we might feel that we are stuck in grief. As we move into back into the River of Life as it flows out of the whirlpool, we mourn, and we move forward (but not move on) into our new normal.

0 Comments

Psychiatrist Colin Murray Parkes and psychologist John Bowlby came up with the four phases of grief model in the 1970s. This is a linear model of grief, like the four tasks of grief and the six R processes of mourning. The real experience of grief generally isn't linear though, and people as they grieve can cycle through different phases, or ping between them like a pinball machine. Shock and numbness After someone dies, whether it's sudden or expected, there is a period of numbness that perhaps helps us to survive the first few days, weeks or months. It's hard to accept the reality of the loss. Yearning and searching In the second phase, we long for our person to return. Our life is full of sadness, anger, anxiety and confusion. We can seem preoccupied. Disorganisation and despair Accepting our loss can leave us without energy, despairing and feeling hopeless, and can make us withdraw. Life feels like it will never get any better. Reorganisation and recovery In the recovery phase, intense sadness starts to withdraw and we may be able to remember the person we lost with more positive feelings. Energy begins to return. I'm not sure about my thoughts on an afterlife, but a few days ago I saw a post about Storm Dudley. Buxton Weather Watch @buxtonweatherw Hi all. A very active few days of weather ahead with both storm Dudley and storm Eunice producing disruptive winds. Storm Dudley arrives today with winds strengthening to 50mph during the afternoon, to around 60mph by 6pm, this lasting through much of tonight and into Thursday. Showers at times during this period however no disruptive rain. Additional care needed if travel over higher routes is planned. However, not expecting storm Dudley itself to produce any major disruption  Just after Tim (Dudley) died, the Beast from the East hit. Tim loved snow, and would call me from downstairs in the shop to say "Snowing!" whenever a few flakes started. I left my village to head south before the roads closed, and just managed to get back a few days later, after being pampered and cosseted by my sister. I remember vividly standing in snowdrifts and looking up at the sky, saying, "Darling, I know God has put you in charge of the weather, and you're having fun, but that's enough." The snow even delayed his post-mortem. The post from Buxton Weather Watch reminded me about this, and I messaged to some friends: "Tim is making himself known around his anniversary. I told God he shouldn't have put him in charge of the weather." These are my continuing bonds with Tim. The continuing bonds model Many models of grief are linear, and go through a range of steps, ending up with acceptance and a new life. While models like the pinball machine and growing around grief do accept that it's more complicated than that, the idea of continuing bonds reflects that we don't just take our grief with us, we take the people that we have lost with us too. It accepts that staying connected with the people we love is normal. The idea of continuing bonds comes from the book 'Continuing Bonds: New Understandings of Grief', edited by Dennis Klass, Phyllis Silverman and Steven Nickman, all experts in grief. Instead of focusing on letting go, continuing bonds talks about building a new relationship with the people that we have lost. This relationship we will take with us for always.

Continuing bonds with our late partners include:

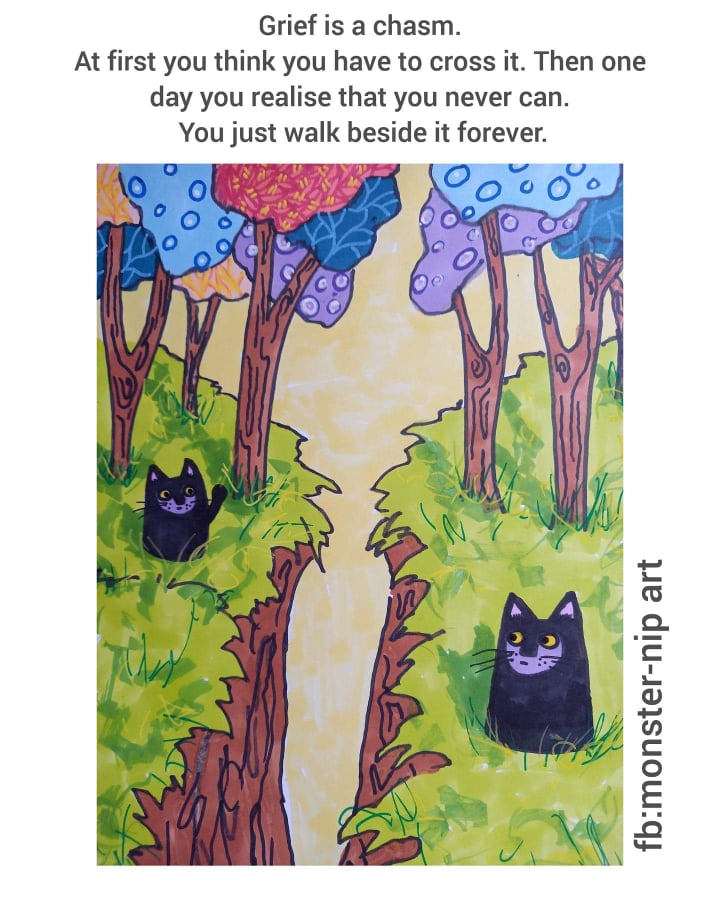

Continuing bonds is a normal part of grief. However, if you feel stuck in grief, or trapped in the connections you have with your loved one, you may have developed what's called complicated grief disorder. This includes exaggerated grief symptoms over a long period, sometimes years or decades. If you feel you have this, it's worth talking to your GP, a counsellor, or a psychotherapist. 'Grief is a chasm' image shared with permission from Nansy Ferrett-Paine of Monster-Nip Art 'Grief is a chasm' image shared with permission from Nansy Ferrett-Paine of Monster-Nip Art

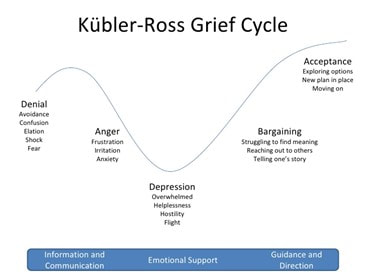

When we are first bereaved, it can feel like a set of old-fashioned scales with all the weight down on one side.  As time goes by, we add things to the other side. The weight of our grief doesn't get any less, but we get a new balance as our life gets bigger (see also Growing around grief). People who haven't been through grief often believe that grief is a linear process. They may have heard of the Kübler-Ross grief model or similar, which look at stages of grief, and think that this is how it works for everyone. Grief really isn't linear. We bounce backwards and forwards through different stages, with triggers such as anniversaries, places, objects or pieces of music sending us one way and another. Margaret Baier and Ruth Buechsel likened this to a pinball machine, where the paddles flip the ball back and forth, sometimes right back to the beginning of the game. This model has helped me understand why sometimes I am thrown back into feelings of sadness and loss, seemingly out of the blue. It also supports something I learned with the growing around grief and Kintsugi concepts – that we carry our grief with us and it becomes part of who we are. As Baier said, "One of the most freeing aspects of this model is the notion that grief is never complete."

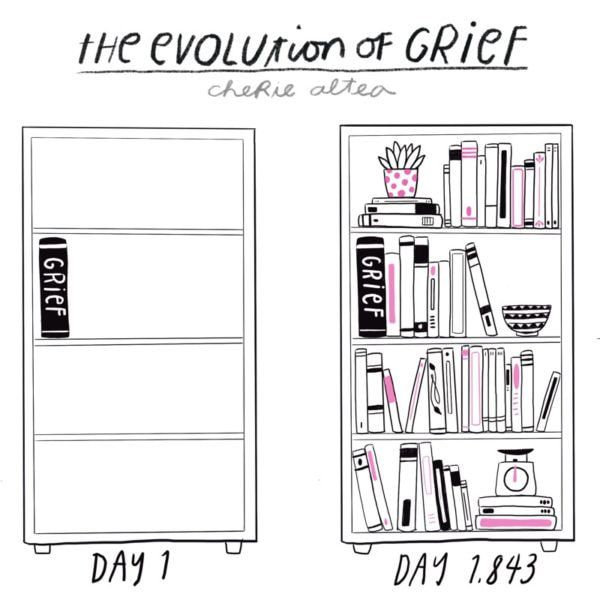

A while after Tim died, a dear friend bought me a Kintsugi kit, complete with a broken bowl. Kintsugi, which translates as 'golden repair', is the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery with a glue dusted with or mixed with powdered gold. Japanese aesthetics has a perspective called wabi-sabi, which appreciates beauty that is "imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete". Those of us who grieve often try to hide our sadness, our brokenness, our emotional and mental scars. Kintsugi as a grief model suggests that we show our scars and treat them as part of us and part of our stories. Living with or alongside our grief, moving forward but not moving on, it's what makes us who we are. Kintsugi "symbolises the truth that repair requires transformation, that the pristine is less beautiful than the broken—and that the shape of us is impossible to see until its fractured, until a wound, like a crack, runs its length." I described it in a blog as "a brave with the stitches showing and the glue not quite set. It's a broken and mended brave… a brave that sees the beauty in the flaws. And while it's a kind of brave that doesn't always withstand a puff of wind, I'm hoping it might be the kind that will stand up to a storm." It took me three and a half years to make the bowl, and I made it to celebrate some major steps in my life after Tim. And I love it. Cherie Altea, an artist based in Singapore, created an image of a bookshelf to illustrate her thoughts on grief. In her own words:

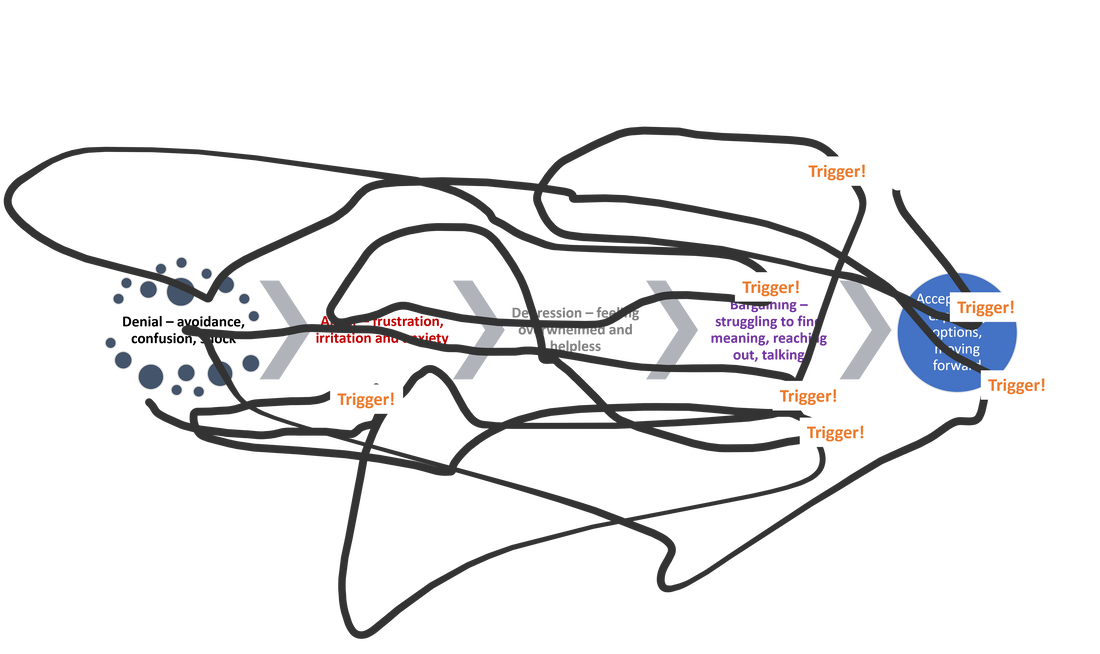

"Imagine that you are this bookshelf and grief were this thick, heavy and permanent book sitting in it. Over time, that book doesn’t change in shape or size. It just stays there and becomes a part of you. As the days and years pass, your library grows around it as everything you add to the shelf becomes another chapter and dimension in your life. The grief, even if you choose to gloss over it, is an indelible presence juxtaposed with the growing collection of things. The spine might fade in the sunlight, yellowing pages will fall out, and its cover will definitely gather dust, but our grief is a book whose pages we can flip through and go back to when we feel compelled to. Without changing in weight, significance or meaning, it shall always and simply be another facet of our existence and one of many stories in our constantly changing life."  Grief can be like a backpack full of rocks. It's heavy, hard to carry, and weighs us down. Sometimes it feels like we can't keep carrying it. But we know can't just put it down. However, over time, we become stronger, develop muscles that help us to cope, to continue. While we still have days that we struggle, we find people, like the Widowed and Young groups, who can help us to carry the weight of this invisible backpack. This is the model that a lot of people pull out – that grief has five stages, and these are denial, anger, depression, bargaining and acceptance. And yes, I've gone through all of these. Denying that it can be real. He was alive last night and he's dead this morning. Fury at him and at the universe that he's gone. Feeling so low that I couldn't believe I could fall lower. Bargaining with the universe to find a reason why it happened to him, and not to the awful people in the world. And acceptance that this is the world I now live in. I didn’t go through them in any order, and I cycled between them, across them and around them. My grief was more like this: The reason that this model doesn't really work for bereavement is that it wasn't actually intended to be about the grief of losing someone we love. Swiss-American psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross' created the model to help terminally ill people to come to term with their own illness and death. David Kessler, her co-author, has worked with her to create models for people who are grieving. He says that there is no typical loss, and not everyone goes through all of the stages, or in any particular order.

|

AuthorI was widowed at 50 when Tim, who I expected would be my happy-ever-after following a marriage break-up, died suddenly from heart failure linked to his type 2 diabetes. Though we'd known each other since our early 20s, we'd been married less than ten years. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed