When we lose someone that we are close to, it of course leaves us grieving. It can also remind us of our own health and mortality. This can turn into health anxiety, which is worrying too much about whether you are seriously ill or are going to become seriously ill. It can affect your day-to-day life. I don't have health anxiety for myself, but I do worry about other people. I've always catastrophised when someone doesn't answer the phone, or is late, or has a symptom, but it's got worse since Tim's sudden death. Early one morning my current partner fell down the stairs. I got her to her feet, and she fainted, slithered through my arms and slumped against the wall. She started making guttural noises, much like Tim did just as his heart stopped. I was shouting at her but couldn't rouse her. I was convinced that she was going to die, and I was mentally rehearsing the 999 call and CPR. Before I could get to my phone, she came round with no awareness that she had passed out, and no aftereffects other than a painful ankle. Once I knew that she was okay, I did the only rational thing and burst into tears. The incident left me with flashbacks for a couple of days. Dealing with health anxiety

Look after yourself Bereavement can also make us care less about our own health, and stop looking after ourselves. This is your reminder that you matter, you are important, and that you need to be kind to yourself and take care of yourself. If you are worried that you are ill, call 111 or talk to your doctor.

0 Comments

Some widows talk about being in a new relationship after loss as being a new chapter. I've done it in the past. But I've changed how I feel about this as it focuses on the only possible happy ever after being that widows find a new love. It implies that a new love fixes us and negates our grief. And chapters are open and shut things, but life just isn't that straightforward and grief stays with us in different forms. So I'm going to talk about stories, because we can have new stories while the old ones still exist.

I also believe that the stories of our lives should be about more than new relationships. They should be about how we move forward, and how we rebuild and develop our lives beyond our bereavements. These kind of new stories aren't a fix – we are works in progress. Our new stories might not be the stories of the lives we wanted, but they are the stories of the lives we have. They are stories of big and small things, and should be celebrated. Our stories are about:

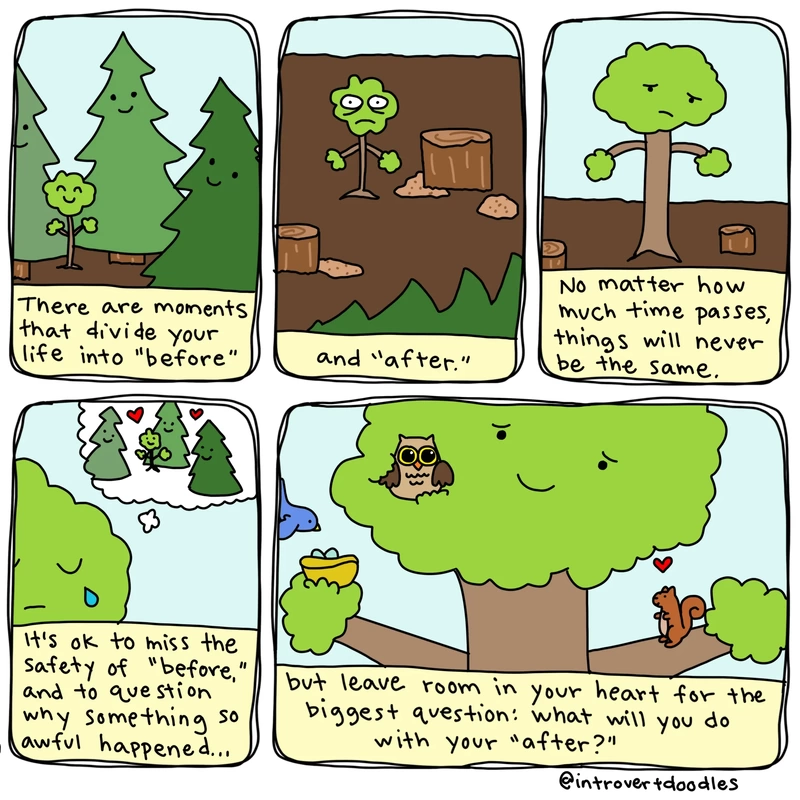

In November 2018, writer and podcaster Nora McInerny gave an amazing TED talk. She founded the Hot Young Widows Club, a US Facebook group for people widowed young. When she asked the group what phrases they hated most hearing in the early days of grief, 'moving on' came close to the top. 'Moving on' implies that the people we have lost are firmly in the past and that's exactly where we should leave them. But, the people we have lost do continue to be present with us; and that's as it should be. It doesn't mean that we are clinging onto a ghost of a dead person, rather that we are influenced by all the people that we have ever known and loved. After Tim died, it felt like everything was gone. But with hard work, amazing support from friends, family plus the charity Widowed and Young, and some psychotherapy, I rebuilt my life. But I didn't 'feel' it. Feeling better felt wrong, because I thought it meant I was moving on and leaving him behind. Forgetting him. Falling out of love with him. Coping without him, the man who I described as the still centre of my turning world. These feelings sabotaged my journey, because I was afraid of letting go of my grief. McInerny's talk changed things for me. I started talking about moving forward, which takes our people with us, rather than moving on, which leaves them behind. Even so, I still had to give myself permission to feel happy. I had to let go of some of my grief. I had to learn that letting go isn't about forgetting them. It's about helping ourselves to live in the now. About understanding that we are who we are because they were in our lives, and because we went through the trauma of bereavement. It helped me to remember that Tim's memories live inside me through my continuing bonds with him. "How long will I grieve? You will always grieve. In time grief changes and rather than be consumed by sadness we remember with love and happiness." The image is by Marzi Wilson of IntrovertDoodles. Buy her book at Hive, and support independent bookshops as well.

Being with someone new, as lovely as he is, as much as he makes me so freaking happy again, in ways that I didn't think possible, has absolutely nothing to do with how much I miss my late partner. How much I wish he was still here! How much I wish myself and my current partner (also a wid) had never ever found ourselves in the position where we join a group for young wids and meet each other. In my blog post Things not to say to a widow, I talk about things people have said about finding another partner: "You are young. You'll find someone new." "They'd want you to be happy." These to me make it seem like replacing a partner is like replacing a worn-out coat, and that having a new relationship makes everything better. In Nora McInerny's wonderful TED Talk, she talks about what she saw in people's reaction to her new relationship: "This audible sigh of relief among the people who love me, like 'It's over! She did it. She got a happy ending. We can all go home." About two and a bit years after Tim died I met someone. It wasn't expected – a friend connected us up over a creative project and we found that we talked often and long into the night. Things were made more complex by all this happening in lockdown, and so by our first 'real' date, a day spent walking around the glorious Yorkshire Sculpture Park, we'd actually been dating virtually for a few months. My ladyspouse and I are getting married. It doesn't take away everything that went before. But it's wonderful. Starting to date as a widow can bring up a whole rush of emotions, and highlight our losses. I had grief attacks and nightmares. I dreamed vividly about Tim. I felt like I was betraying Tim, and I worried about what people would think. I felt very vulnerable and my emotions about my new partner swung around wildly. When we first kissed, it was the first kiss since Tim died, and I felt a spike of guilt. When we first slept together, I had to fight intrusive memories, as the bedroom is where Tim died. That took a lot of grounding. If you start dating, remember to be kind to yourself. Take things steady. Keep safe. But also enjoy. We've already faced the worst and survived and sometimes we need to seize the moment. After all, we know that life is short. "Our hearts are amazing things – they can expand to fit new people in it – no one questions if a new mother still loves her husband or other children, it is taken for granted that they have enough for the new addition. In the same way in the widowed world being lucky enough to find love again in no way diminishes what we once had – there is room enough in our hearts for the new alongside the old."

This is one of a pair of blogs - see also Clearing after bereavement: My story

Clearing after bereavement is hard. It’s full of triggers and tough memories and it's not something we ever imagined ourselves to have to do. Don't feel guilty clearing things out. This is your home, and is where you need to feel comfortable living. There is no single right time for doing it. For some people, sorting out a partners' belongings happens the day after the death, for some it takes years, for others, it never happens. It also doesn't always happen all at once – it could be in two goes, or six goes, or ten goes, or sometimes a lifetime of goes. I did some sorting, got rid of some clothes and changed the layout of the bedroom, but it took about two years, the death of a friend, and a global pandemic for me to tackle it properly. I did the clearing on my own, as it meant that I could work at my own speed, and not have to stop to explain things or answer questions. I did have a couple of friends on hand who I could message for support, or to show pictures of my progress. I also took frequent breaks as it was both physically and emotionally exhausting. But it's not the same for everyone – you might want to call in a friend or a family member for practical help, or just moral support. For some people, the process has to involve other people. This can be hard, and will need a lot of conversations and patience from everyone involved. When you start clearing, divide things into categories:

Break the process down into manageable tasks, and start with the things with the fewest memories attached to them. Do an hour a day or a day a week, and tackle it room by room, or even cupboard by cupboard. Step away for a bit whenever you need to – go for a walk, have a nap, watch or listen to something. If you are not working to a deadline, don't feel rushed – if you're not sure about whether to keep something or get rid of it, put it away until the next round of clearing. Some people will be under a deadline to sort things out – there may be a date to leave the property, or there may be pressure from other family members. If you have this kind of stress, enlist friends to help and to support you. Create a memory box for things you want to keep but don't want to see every day, and take photos of things that are important memories, but you don't want to keep. Be prepared for the grief attacks. And for the unexpected. But also, enjoy the happy memories. However hard it is, decluttering and rearranging your home can be a very positive experience. I found that it helped me to process my grief, which I didn't expect, and to reclaim the house as my home. Clothes and jewellery

Toiletries

CDs, DVDs, games and books

Phones, tablets and computers

Electrical equipment

Other items

This is one of a pair of blogs - see also Clearing after bereavement: The practical side Tim died in the bedroom, in our bed, and the room was full of triggers. The day of his death, a friend stripped the bed, washed everything, and remade it for me. I made myself go back and sleep in it that night, but I knew I had to replace it – the bed, the mattress, the bedding – and rearrange the room. Tim sold second-hand books, and the shop was on the ground floor of the house. Walking through his bookshop, seeing the counter where Tim would always be – smiling at me when I brought him a cup of tea, calling me down if there was something exciting that had come in – was so hard. Friends helped me run it for a while, but I knew that I couldn't keep it going for long, and I had to sell the business. Fortunately, the amazing Juliet Waugh bought it and it's now in another location in the village, with Tim's face presiding over the customers. The money paid for my Master's degree. The house was still full of stuff belonging to Tim. He sat somewhere on the borderline between being a hardcore collector and a hoarder, and he found it very hard to let go of things. Everything had a sentimental connection, and most things he had were for a reason – they were books he would read one day, magazines that he wanted a complete run of, model kits that he would make, or things that might come in useful. It was overwhelming me. The COVID-19 lockdown came two years after Tim's death and around the time that an old and very close friend died from glioblastoma, a very unpleasant and usually fatal brain tumour. I had little freelance work and I felt truly alone. After hitting a very deep low, the way I coped was by sorting the house. This involved making a lot of very tough decisions. Getting rid of clothes was difficult. They are so personal – and somehow shoes and ties were the most personal of all. My sister Judith had helped me run through them a few months after he died, and she took some to her local charity shop, so I didn't have to see them when I went into town. Judith made me a bear out of his favourite jumpers, with a waistcoat made from his ties. It took me going through them another two times before I got it down to the few things I really wanted to keep. The next things were magazines and race programmes. These were in every room of the house, mostly in labelled boxes, but sometimes just in piles. They were in cupboards, under beds, in drawers. In the bathroom. On the shop counter. Everywhere. When I collected them together, they filled one of the rooms of the empty shop. Full of guilt, I sold them to a magazine seller in London for a sadly small amount, and it took him three journeys to take them away. And then on to the house. There wasn't a room that didn't remind me of Tim. I didn't intend to erase him, but I needed to reclaim my home, and reignite my love for its 15th century beauty. I started a clear out, which some days reduced me to tears as I picked up things that I knew had meant so much to him. I started piles to keep, to throw away, to sell, to donate to charity shops. I made a memory box of things that I couldn't bear to let go of, but I didn't want to see every day. I cleaned, painted, moved furniture around. And gradually created a home that brought me joy. The next step is finding a new home for my wedding dress. I loved it, but it's time for it to make someone else's day perfect. The thing that surprised me about lockdown, and about sorting out the house, is how it helped me process grief. A friend said to me that she saw the change in the house as a reflection of the change in the inside of my head. I, and my house, are still a work in progress. But at least it's a work in progress where there is somewhere to sit down. Some days we potter along. Everything is, if not marvellous, then pretty much okay. Then seemingly out of the blue comes an attack of grief. It feels as if you are standing on a beach and a wave has come up and caught you behind the knees, throwing you off balance. Grief attacks can seem overwhelming.

What triggers a grief attack? A few months after Tim died, I watched a Lancaster fly across my village. I knew that Tim would have loved it, would have had so many stories about it, and I dissolved into grief. I could put my big girl pants on and be 'brave' for a birthday or an anniversary, but I couldn't prepare myself for opening a box and finding the piece of paper and yellow roses that he left on my desk to celebrate the anniversary of our first kiss. Or the realisation that the washing contained only my clothes, not both of ours. Or finding the half-made Airfix model or the half-read book. Grief attacks can be triggered by the biggest and the smallest things – thinking about milestone dates, suddenly hearing a piece of music on the radio, someone saying a particular phrase, seeing someone wearing a particular colour or style. Even a particular kind of weather can trip off a grief attack. When a grief attack hits, sometimes we need to just 'sit' in the grief, and let it wash over us. Cry if we need to. Be gentle with ourselves. Remember that the attack will pass. And then breathe slowly, and use grounding techniques to return to the here and now.  After Tim died, I became so tired. The kind of tired that squashes you flat. The kind of tired that it felt like even my bones hurt. Feeling this exhausted can be scary. But it is a normal part of grief. Why does grief make you tired? You're in shock A psychological shock triggers the fight, flight or freeze response. Our bodies fill with the stress hormone cortisol, desensitising us and putting us on alert. After a bereavement, particularly a sudden and unexpected one, our cortisol levels remain high for a prolonged period of time, leaving us exhausted. Your brain has so much to process Our brains get tired when they are being asked to process information all the time – every decision requires energy. So grief exhaustion is both physical and mental. You can't sleep Grieving often means your head just won't stop – it's full of spinning thoughts and tough memories. You may also be having nightmares, flashbacks or intrusive memories. All of these will affect your sleep. There's so much to do Bereavement leaves us with a lot of admin, from bank accounts to businesses, and from phone contracts to funeral arrangements. There is so much that needs to be completed, and some things must be done in specific timelines. Losing someone also means losing their help at home. This can include routine jobs around the house and caring responsibilities. For some people, bereavement means having to find somewhere else to live, sometimes at short notice. You are hypervigilant Hypervigilance is a state of extreme alertness where you are constantly assessing the environment for threats, both real and perceived. You may feel that since you have been through a traumatic event, what's to stop another? Hypervigilance can be a symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). It is exhausting in itself, as well as making it hard to relax or sleep. You aren't eating properly It can be hard to eat well when you are grieving – it may not seem worth it to cook for one, or your appetite may not be what it was. Not having enough of the right kind of nutrients leaves you without energy. Both your diet and your alcohol intake can also affect the depth of your sleep. What to do?

I'm a writer by trade. Science writing pays the bills and fiction provides the creativity. After Tim died, I used my blog as part of my grieving, sometimes writing to Tim, sometimes documenting the steps I took, other times just setting down in words how I was feeling. There were bees in there too. Writing The Widow's Handbook is helping me work through parts of my grief, and helping me to understand why I feel how I feel.

Writing your grief Writing can be a way of making sense of the world, of getting feelings out of our heads and putting them in order, of processing our grief. It can help us to manage the chaos in our heads. Writing can trigger emotions, so be prepared for what I call grief attacks, those moments that feel like waves of the sea catching you behind the knees and sweeping you off your feet. Writing can actually help our health – it can boost our immune systems. It can also improve our mood. While depression isn't the same as grief, a study of people with depression showed that writing every day lifted their mood. Getting writing Just sit down and do it, with paper and pen or pencil, or on a computer or tablet. Whatever works for you. Don't worry about whether what you are writing is any good. Later you can edit it if you want others to read it, or if you want to keep it as a record, but for now, just pour it out on the page. Writing for yourself means that you can be more open and honest than you perhaps can be with other people. You can just let out exactly how you feel, whether that's anger, relief, hope or heartbreak. How to start

|

AuthorI was widowed at 50 when Tim, who I expected would be my happy-ever-after following a marriage break-up, died suddenly from heart failure linked to his type 2 diabetes. Though we'd known each other since our early 20s, we'd been married less than ten years. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed