|

When I stepped out of the door the morning that Tim died, I couldn’t believe that village life could go on as normal when my life had so suddenly and drastically changed. But it did.

Over the years since 2018, I have rebuilt my life, embracing my sexuality, going back to university, meeting and marrying my wonderful Dee, and making a fresh start in a new location. All of these changes have left me sometimes feeling that I'm living two parallel lives. There's the life that I live now and the other that carried on, where I am still married to Tim. We still live above the bookshop. And he is pricing books downstairs. The life we live without them can leave us feeling guilty and resentful. About the what-ifs, the things we did or didn’t say, simply that we survived. And for going on without them. Going to work. Seeing friends and family. Making changes to the house. Enjoying ourselves. Doing things that they will never do, in places that they will never see, and making decisions that they will never know. There’s nothing I can say that makes this better. As Tim would say, it is what it is. We continue without them, moving forward but not moving on. And as a community, we do it together.

0 Comments

I moved house a fortnight ago, from the house that Tim and I bought to house his bookshop, and where he died suddenly and unexpectedly, to a house near the sea that I hope that my wife and I will make into our forever home. The whole process, from making the decision that we wanted a house that was chosen by both of us, rather than chosen by me, to opening the door here for the first time, actually only took around seven months, but felt so much longer. It was exhausting and involved builders vanishing leaving work unfinished, arguments with the local National Park Authority, and solicitors (not ours) causing delays. It was also a very emotional process, as it meant moving away from a friendship group that carried me through some really hard times, as well as leaving behind a place that had been very important to Tim and me.

I got rid of a lot of stuff, because that’s what you do when you move, and some of that was a huge wrench. But it also was oddly freeing at times. Packing felt interminable, and every time I thought I was nearly there, I turned round and saw more. Dee fell ill with a horrible viral infection, and then I got it two days before completion date. But we got there. The wife, dogs and the van went off, leaving me alone in the empty house with the cats. Friends scooped me up, fed me and gave me a bed. And then on the day of the move, I drove 146 miles in a two-seater sports car packed to the gunnels with all the last bits and pieces, along with a pack of cold and flu capsules, a lot of Haribo, and two profoundly irritated cats. One sulked, the other yowled for 93% of the journey, and glared silently for the other 7%. I was worried that I would lose Tim in the move, and in some way, lose me as well. But now the house is beginning to feel like mine, rather than someone else’s. I have my office in place. There are touches of Tim here. And the sulking cat is asleep on the bed. Five years ago this morning, Tim took his last breath. I've written about his sudden death, packing his bag for the last time, how life carries on when yours has stopped, coping with clearing the house, dealing with the What Ifs, giving myself permission to feel happy, and about how my life changed.

As always, I found the run up to the anniversary to be worse than the anniversary itself, but this year it has felt different. I have moved forward – I am still working as a freelance medical writer, but I am trying (though not always succeeding) to spend more time writing creatively. I have let part of what was his bookshop to a small local business selling stoves and fireplaces. I am selling his book collection to be able to invest money into a new house. But I haven't moved on –I am keeping some books and other things to remember him by, and he travels with me. After all, he taught me that I deserve love. I have a new love, Dee, and we married last summer. We are building new memories. We are planning to sell this house and buy a new house together to create a place that is ours. This will be a wrench as it was mine and Tim's home and workplace, but it is the right thing to do. Being with Dee hasn't displaced my old love. Tim is still in my heart, I cherish his memory and the memories we made together. Grief is still there. It is something that we as widows walk alongside. But I now can see it as a quiet companion rather than a raw and bleeding wound. I was widowed in a February, and the second half of that year was tough, with a run of firsts – my birthday and our wedding anniversary on the same day in mid-September, his birthday in December, Christmas, and then the New Year's Eve party that we'd both been going to since our twenties. After that, January and February felt like a countdown to his death date. I heaved a sigh of relief once I got into March – the firsts were all over. But I hadn't realised that firsts aren't all over in that first year. There are things that come around less frequently, such as weddings, funerals (hopefully), work trips, buying furniture or decorating, and these can bring on the grief attacks.

The second year of grieving is very different from the first. In some ways it is easier, and in some it can be a lot harder. The second year was the division between 'Tim died earlier this year', to 'Tim died last year', or 'Tim died just over a year ago'. The second year was the time that it was all real, and I had to accept that this was what my life was now. That that grief would be part of me for the rest of my life. And that I had to find out who I was again. I was achingly lonely, even though I was surrounded by friends. I was often tired, and I still had widow brain, which made concentrating hard. I tried to fill up my time with work and took on too much, which led to a major crash in mood and having to drop a couple of freelance writing projects, which meant in turn I lost a couple of clients. I had flashbacks and nightmares going back to the morning Tim died, and I struggled with thoughts about what was happening to him after death. My depression hit a real low, and I struggled with thoughts of suicide, but wasn't able to access the mental health support I needed despite this. The second year can be where the secondary losses become clear. As widows, we lose our past, our present and our future, and for some people this becomes more concrete in the second year as they lose homes, struggle to pay mortgages, are no longer able stay in their jobs, find their support circles are receding, or find that they have lost contact with friends and family. Some widows I know found that people's expectations changed – they expected them to be 'moving on', and 'getting over it'. People who haven't been widowed don't always understand that there is no timeline to grief, and that, while we might move forward, we don't move on from the people that we have loved and lost. Some things were easier, however. The pain of his death was a lot less raw. I cried less, and I could function more. I slept better, and started to cook some of the time, rather than live on ready meals and things out of tins. I also found that I could start to plan things to look forward to, provided they weren't too far in the future. One of the things that's important about the second year of grief is that you need to be patient with yourself, and that you are still allowed to ask for help and support. Moving into the third year of grief The third year was a year of a lot of change. It was the year of the Covid-19 lockdowns, and while I felt the most alone I had ever been, and I lost a lot of work, it created a liminal space that allowed me to grieve and to think about what came next. It also allowed me to make the house into somewhere I wanted to stay. I managed to access psychotherapy and this made an amazing difference as well. I've known that I was attracted to both men and women since my 20s. Actually… the crushes on a couple of truly awesome female teachers in my teens might mean I knew it before, but didn't realise what it meant. The first time I came out as bi to a lesbian friend, she told me that bisexuality is just a phase, and I should pick a side. Consequently, I didn't tell anyone else for a long time.

I married Paul at 24, which now seems impossibly young. Over a decade our marriage fell apart. Tim, who I'd known for many years, helped me through depression and a divorce, and we drifted from being very close friends to falling in love. While I spent this period of my life 'straight passing', I was still bisexual. Tim knew about my sexuality and loved me all the same. He died suddenly at 50, after we'd only been married nine years, and my life crumbled. Some friends had known that I was bi, but I wasn't really out. Even before Tim died I'd been feeling that I was somehow living a lie, and betraying who I was. As I started to build another life, I became more open about what I was. And when I started seeing a woman, I couldn't really hide any more. The responses to me coming out, as well as 'picking a side', ranged from total acceptance and 'when I met you, my gaydar pinged, but I assumed that I was wrong – I see now', to 'I don't understand – you used to be married to a man but he's dead' and 'does that mean you were sleeping with women when you were married to your husband?' Now I am married to a woman, I guess I'm 'lesbian passing', and I suspect that many people think I have made a major lifestyle change, finally picked a team, or only just realised I'm gay. This isn't helped by bi erasure, and by the media and entertainment tropes about bisexuals showing them (us) as cheating, confused, greedy, promiscuous, villainous, unable to stay faithful, or just bi-curious. And that's just the women. The bisexual men are much less visible. However – I am proudly and defiantly queer. I am bisexual, from the pink and purple in my hair down to my awesome Pride Converse. Have a wonderful Celebrate Bisexuality Day! #CelebrateBisexualityDay #BisexualPrideDay #BiVisibilityDay Some widows talk about being in a new relationship after loss as being a new chapter. I've done it in the past. But I've changed how I feel about this as it focuses on the only possible happy ever after being that widows find a new love. It implies that a new love fixes us and negates our grief. And chapters are open and shut things, but life just isn't that straightforward and grief stays with us in different forms. So I'm going to talk about stories, because we can have new stories while the old ones still exist.

I also believe that the stories of our lives should be about more than new relationships. They should be about how we move forward, and how we rebuild and develop our lives beyond our bereavements. These kind of new stories aren't a fix – we are works in progress. Our new stories might not be the stories of the lives we wanted, but they are the stories of the lives we have. They are stories of big and small things, and should be celebrated. Our stories are about:

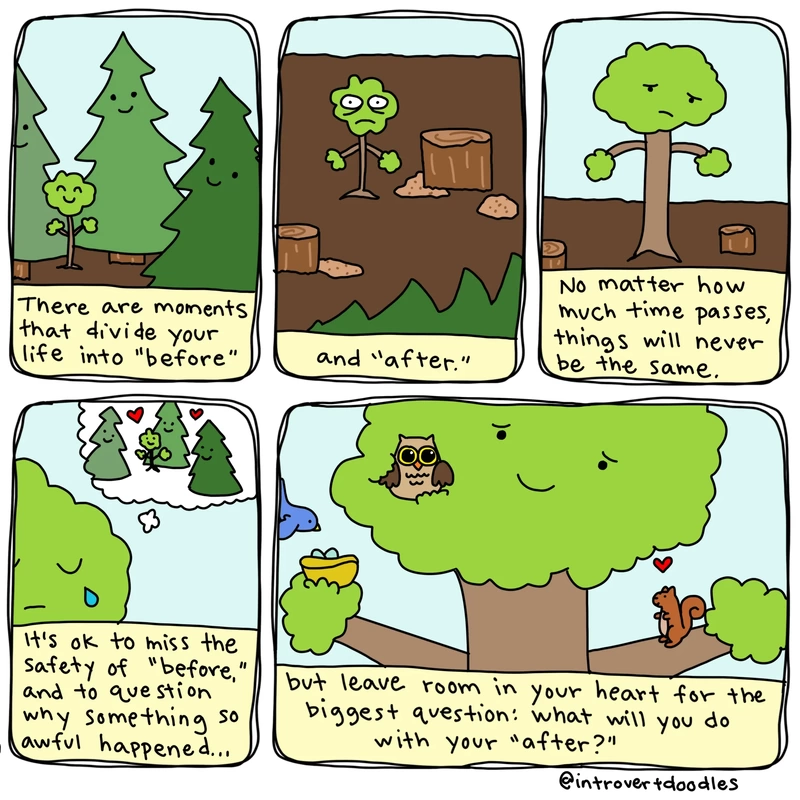

In November 2018, writer and podcaster Nora McInerny gave an amazing TED talk. She founded the Hot Young Widows Club, a US Facebook group for people widowed young. When she asked the group what phrases they hated most hearing in the early days of grief, 'moving on' came close to the top. 'Moving on' implies that the people we have lost are firmly in the past and that's exactly where we should leave them. But, the people we have lost do continue to be present with us; and that's as it should be. It doesn't mean that we are clinging onto a ghost of a dead person, rather that we are influenced by all the people that we have ever known and loved. After Tim died, it felt like everything was gone. But with hard work, amazing support from friends, family plus the charity Widowed and Young, and some psychotherapy, I rebuilt my life. But I didn't 'feel' it. Feeling better felt wrong, because I thought it meant I was moving on and leaving him behind. Forgetting him. Falling out of love with him. Coping without him, the man who I described as the still centre of my turning world. These feelings sabotaged my journey, because I was afraid of letting go of my grief. McInerny's talk changed things for me. I started talking about moving forward, which takes our people with us, rather than moving on, which leaves them behind. Even so, I still had to give myself permission to feel happy. I had to let go of some of my grief. I had to learn that letting go isn't about forgetting them. It's about helping ourselves to live in the now. About understanding that we are who we are because they were in our lives, and because we went through the trauma of bereavement. It helped me to remember that Tim's memories live inside me through my continuing bonds with him. "How long will I grieve? You will always grieve. In time grief changes and rather than be consumed by sadness we remember with love and happiness." The image is by Marzi Wilson of IntrovertDoodles. Buy her book at Hive, and support independent bookshops as well.

Being with someone new, as lovely as he is, as much as he makes me so freaking happy again, in ways that I didn't think possible, has absolutely nothing to do with how much I miss my late partner. How much I wish he was still here! How much I wish myself and my current partner (also a wid) had never ever found ourselves in the position where we join a group for young wids and meet each other. In my blog post Things not to say to a widow, I talk about things people have said about finding another partner: "You are young. You'll find someone new." "They'd want you to be happy." These to me make it seem like replacing a partner is like replacing a worn-out coat, and that having a new relationship makes everything better. In Nora McInerny's wonderful TED Talk, she talks about what she saw in people's reaction to her new relationship: "This audible sigh of relief among the people who love me, like 'It's over! She did it. She got a happy ending. We can all go home." About two and a bit years after Tim died I met someone. It wasn't expected – a friend connected us up over a creative project and we found that we talked often and long into the night. Things were made more complex by all this happening in lockdown, and so by our first 'real' date, a day spent walking around the glorious Yorkshire Sculpture Park, we'd actually been dating virtually for a few months. My ladyspouse and I are getting married. It doesn't take away everything that went before. But it's wonderful. Starting to date as a widow can bring up a whole rush of emotions, and highlight our losses. I had grief attacks and nightmares. I dreamed vividly about Tim. I felt like I was betraying Tim, and I worried about what people would think. I felt very vulnerable and my emotions about my new partner swung around wildly. When we first kissed, it was the first kiss since Tim died, and I felt a spike of guilt. When we first slept together, I had to fight intrusive memories, as the bedroom is where Tim died. That took a lot of grounding. If you start dating, remember to be kind to yourself. Take things steady. Keep safe. But also enjoy. We've already faced the worst and survived and sometimes we need to seize the moment. After all, we know that life is short. "Our hearts are amazing things – they can expand to fit new people in it – no one questions if a new mother still loves her husband or other children, it is taken for granted that they have enough for the new addition. In the same way in the widowed world being lucky enough to find love again in no way diminishes what we once had – there is room enough in our hearts for the new alongside the old."

|

AuthorI was widowed at 50 when Tim, who I expected would be my happy-ever-after following a marriage break-up, died suddenly from heart failure linked to his type 2 diabetes. Though we'd known each other since our early 20s, we'd been married less than ten years. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed