|

First published on The House of Correction blog in November 2018

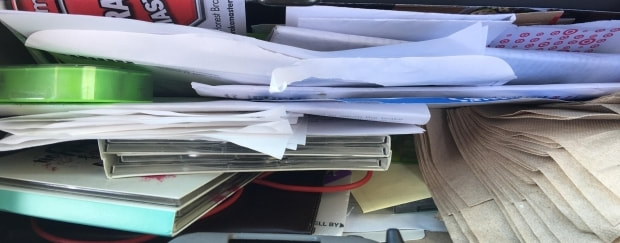

I've just bought a new shredder, and now my office carpet looks like it's been hit by a cellulose snowstorm. I'm going through a huge box of papers and getting rid of anything older than five years. There's a satisfaction of pushing sheets of paper into its tooth-lined maw, and filling paper sacks with shreddings for recycling. It is making me think of things that are no more. Cars, houses, cats, jobs. And marriages. There's a lot of Tim's paperwork in here. Payslips, bank statements, bills, receipts, car documentation. And always the challenge of seeing his writing. I can't keep it all but there is part of me that feels guilty getting rid of it, as if I am erasing him. There are some things I'm keeping, though. An old driving license. His invitation to his cousin's 21st birthday party. The receipt from a wonderful; holiday in the Loire Valley. Notes that he left on my desk. It's a balance between preservation and decluttering, and the most valuable things there are I still have. My memories of him.

0 Comments

This is one of a pair of blogs - see also Clearing after bereavement: My story

Clearing after bereavement is hard. It’s full of triggers and tough memories and it's not something we ever imagined ourselves to have to do. Don't feel guilty clearing things out. This is your home, and is where you need to feel comfortable living. There is no single right time for doing it. For some people, sorting out a partners' belongings happens the day after the death, for some it takes years, for others, it never happens. It also doesn't always happen all at once – it could be in two goes, or six goes, or ten goes, or sometimes a lifetime of goes. I did some sorting, got rid of some clothes and changed the layout of the bedroom, but it took about two years, the death of a friend, and a global pandemic for me to tackle it properly. I did the clearing on my own, as it meant that I could work at my own speed, and not have to stop to explain things or answer questions. I did have a couple of friends on hand who I could message for support, or to show pictures of my progress. I also took frequent breaks as it was both physically and emotionally exhausting. But it's not the same for everyone – you might want to call in a friend or a family member for practical help, or just moral support. For some people, the process has to involve other people. This can be hard, and will need a lot of conversations and patience from everyone involved. When you start clearing, divide things into categories:

Break the process down into manageable tasks, and start with the things with the fewest memories attached to them. Do an hour a day or a day a week, and tackle it room by room, or even cupboard by cupboard. Step away for a bit whenever you need to – go for a walk, have a nap, watch or listen to something. If you are not working to a deadline, don't feel rushed – if you're not sure about whether to keep something or get rid of it, put it away until the next round of clearing. Some people will be under a deadline to sort things out – there may be a date to leave the property, or there may be pressure from other family members. If you have this kind of stress, enlist friends to help and to support you. Create a memory box for things you want to keep but don't want to see every day, and take photos of things that are important memories, but you don't want to keep. Be prepared for the grief attacks. And for the unexpected. But also, enjoy the happy memories. However hard it is, decluttering and rearranging your home can be a very positive experience. I found that it helped me to process my grief, which I didn't expect, and to reclaim the house as my home. Clothes and jewellery

Toiletries

CDs, DVDs, games and books

Phones, tablets and computers

Electrical equipment

Other items

This is one of a pair of blogs - see also Clearing after bereavement: The practical side Tim died in the bedroom, in our bed, and the room was full of triggers. The day of his death, a friend stripped the bed, washed everything, and remade it for me. I made myself go back and sleep in it that night, but I knew I had to replace it – the bed, the mattress, the bedding – and rearrange the room. Tim sold second-hand books, and the shop was on the ground floor of the house. Walking through his bookshop, seeing the counter where Tim would always be – smiling at me when I brought him a cup of tea, calling me down if there was something exciting that had come in – was so hard. Friends helped me run it for a while, but I knew that I couldn't keep it going for long, and I had to sell the business. Fortunately, the amazing Juliet Waugh bought it and it's now in another location in the village, with Tim's face presiding over the customers. The money paid for my Master's degree. The house was still full of stuff belonging to Tim. He sat somewhere on the borderline between being a hardcore collector and a hoarder, and he found it very hard to let go of things. Everything had a sentimental connection, and most things he had were for a reason – they were books he would read one day, magazines that he wanted a complete run of, model kits that he would make, or things that might come in useful. It was overwhelming me. The COVID-19 lockdown came two years after Tim's death and around the time that an old and very close friend died from glioblastoma, a very unpleasant and usually fatal brain tumour. I had little freelance work and I felt truly alone. After hitting a very deep low, the way I coped was by sorting the house. This involved making a lot of very tough decisions. Getting rid of clothes was difficult. They are so personal – and somehow shoes and ties were the most personal of all. My sister Judith had helped me run through them a few months after he died, and she took some to her local charity shop, so I didn't have to see them when I went into town. Judith made me a bear out of his favourite jumpers, with a waistcoat made from his ties. It took me going through them another two times before I got it down to the few things I really wanted to keep. The next things were magazines and race programmes. These were in every room of the house, mostly in labelled boxes, but sometimes just in piles. They were in cupboards, under beds, in drawers. In the bathroom. On the shop counter. Everywhere. When I collected them together, they filled one of the rooms of the empty shop. Full of guilt, I sold them to a magazine seller in London for a sadly small amount, and it took him three journeys to take them away. And then on to the house. There wasn't a room that didn't remind me of Tim. I didn't intend to erase him, but I needed to reclaim my home, and reignite my love for its 15th century beauty. I started a clear out, which some days reduced me to tears as I picked up things that I knew had meant so much to him. I started piles to keep, to throw away, to sell, to donate to charity shops. I made a memory box of things that I couldn't bear to let go of, but I didn't want to see every day. I cleaned, painted, moved furniture around. And gradually created a home that brought me joy. The next step is finding a new home for my wedding dress. I loved it, but it's time for it to make someone else's day perfect. The thing that surprised me about lockdown, and about sorting out the house, is how it helped me process grief. A friend said to me that she saw the change in the house as a reflection of the change in the inside of my head. I, and my house, are still a work in progress. But at least it's a work in progress where there is somewhere to sit down. |

AuthorI was widowed at 50 when Tim, who I expected would be my happy-ever-after following a marriage break-up, died suddenly from heart failure linked to his type 2 diabetes. Though we'd known each other since our early 20s, we'd been married less than ten years. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed