|

Warning – contains swearing

Gluttony, often mistaken for greed (part 1 and part 2), is an excess in eating or drinking (hunting for definitions brought me to crapulous, a brilliant word). Being bereaved is rough, and sometimes we need that extra bit of comfort. I know that I took to comfort eating, comfort drinking and comfort shopping as coping mechanisms when Tim died. This piece isn't about shaming or guilting people for their choices. Being bereaved is hard enough, without a blogger telling you what to do. It's just here if this is something that you are thinking you want to consider, or to change. Comfort eating, emotional eating or stress eating Food is my go to when I'm grieving, depressed or stressed. And it's generally not classy food – it's cheese straight out of the fridge, toffee popcorn in handfuls, or crisps in huge bags. In these situations, I also don't really notice what I'm eating, I just notice when I reach for the next handful and it's gone. I have ADHD, and impulse control is not one of my strong points – if I see food in the cupboard, I want it and I don't want to wait. Comfort eating when we are low feels like a form of self-care, because it triggers the reward systems in our brains, and makes us feel better, at least for a moment. And in the early days of grief, when I had no appetite at all, getting calories in any form was a good thing. Not eating properly, if it lasts long term, can have an impact on our mental and physical health. Guilt, shame and regret can be part of our feelings of grief anyway, and if we are feeling guilty about what we eat, that could just pile on top. If you want to make a change Cooking and eating after loss is hard, whether it's the challenge of cooking for one rather than two, the additional costs of food shopping for one rather than buying in bulk, or simply a loss of appetite or missing what used to be a shared pleasure. Meal kits for one, or even just a new cookery book can help with getting back into the habit of cooking, and batch cooking helps to fill the freezer for those days that you just can't face the chopping board. Signing up for a healthy eating and exercise program (I'm using the Glean App) is helping me to structure my eating and encouraging me to exercise, and the peer support works to keep me on track. But it's whatever works for you and makes you feel better. Emotional drinking A glass of wine, a gin and tonic or a really good single malt is my treat to myself, and I love how it tastes and how it makes me feel. There were times after Tim died, or when I've been coping with depression, that I drank a lot to relax, to numb how I felt, or to be able to fall asleep. Like comfort food, alcohol releases the feel-good chemicals in our brains. It calms anxiety and slows down overthinking. It takes the edge off. But too much of a good thing isn't always a good thing, and too much alcohol impairs judgement, and can cause health problems and problems at work or with friends and family. If you want to make a change If you want to reduce what you drink, there are apps to help you work out how much you actually drink, and help you cut down or stop drinking, such as Try Dry from Alcohol Change UK, MyDrinkaware, or the Drink Free Days app from the NHS. Some people find reducing what they drink is too hard and it's simpler to stop drinking altogether, and apps like these can help too. If you feel that you are dependent on alcohol, or that alcohol is harming you, talk to your GP or contact an organisation like UK SMART Recovery, Alcohol Change UK or FRANK. Comfort shopping or retail therapy I've talked to other widows about 'pressing the fuck-it button', which describes moments of retail therapy that make us feel good, from gorgeous boots during lockdown when there was nowhere to go (yes, that was me), to a new car or campervan. You can even buy the button. Buying things can help us to reclaim what were shared spaces as our own. Tim died next to me in bed, so one of my first purchases was a new bed and new bedding. But retail therapy can also leave us with a stack of things we will never use or wear. Being widowed can leave people with a reduced income, or push them into poverty, and when emotional spending gets to be too regular, it can make a huge economic impact. If you want to make a change Monitoring spending highlights how much often we are splashing the cash. Taking shopping apps off your phone, delaying purchases by 48 hours to give you thinking time, and sticking to a budget so that you can shop, just not too much, can slow the spending down. Another option is to pledge to buy only second hand, and to sell what you aren't using, either to put in your slush fund or to raise money for charity.

0 Comments

As widows, we should be proud of ourselves. We have got through some of the worst possible experiences.

Be proud of what you have achieved today. Today may be a bad day, and if it is, be proud that you are still here. You have survived another day. Today may be a okay day. Be proud that you are clean and are drinking tea (other beverages are available). Today may be a good day. Be proud of looking after yourself, looking after other people, going to work, shopping, acting, singing, creating something, changing your life, changing the world. Whatever you have done, however small, however huge, you did it. Be proud. I'm proud of you. I've never been very good at asking for help – even as a kid I would say "I can manage it on my own". When I was widowed, I hated asking for help even more.

Sometimes I just couldn't frame what I was asking for because I was so low. Sometimes I didn't want to face people. But sometimes it was pride – I was ashamed that I couldn’t do it on my own. It was also pride that I didn't want to ask people into the house. It was a mess – because of the amount of stuff there was, because I wasn't looking after it and myself, because I didn't have time as I threw myself so deeply into work as a way to cope. Slowly, I learned that it really is okay to ask for help, and that there is no shame in asking. That helping makes people feel good, and it helps them to grieve too. And that refusing help can mean that people don't offer to help you, or others, in the future. I still don't find it easy, and I can be clumsy in asking, but I am a little better at it now. Hearing "what can I do", especially in those first few blurred days and weeks, is such a hard question to answer. One of the most useful suggestions from a friend when Tim died was to get a pad of sticky notes and a pen and to write down what I needed help with, and stick the note up on the wall. Then when people asked, I could just direct them to the wall. The word sloth comes from the Latin word acedia, which means lack of care, indifference or carelessness. This post isn't about not caring for ourselves (that's going to be in the Gluttony post), it's about learning not to care quite so much about what others think to protect our own health, both mental and physical.

I’m a people pleaser and a diplomat. I was brought up to think about how people feel, and put their feelings and needs before mine. I found myself managing other people's grief as well as my own. Treading around them gently, reassuring them, looking after them, while inside my head I roared "He was mine! This grief is mine!" At an extreme, these people become grief vampires or grief hijackers, who twist any grief conversation around to be about them rather than about you. It's okay to say no to things. It's about putting yourself first for once. You are allowed not to accept every invitation, and if you do accept invitations and you think they will be tough, have a plan – arrive early so you don't have to walk into a busy room of people and so you can check out somewhere to hide if you need a break. Arrange to meet people outside so you have someone to walk in with. Drive so you can leave when you want, or book a taxi for a specific time – you can always rebook it if you need to. Conversely, it's okay to enjoy yourself. We no longer have to obey a strict etiquette of mourning that dictates what we wear or how we behave in a specific mourning period. We can laugh, sing and dance if we want to, but always and only if we want to. We need to put ourselves first. Warning. Some swearing.

As I said in part 1, people have some odd perceptions of widows. There is an idea that widows, especially widows without children, cash in pensions and life insurance and live giddily, splashing the cash and living the life of Riley. Flash car. Foreign holiday. This idea of all widows being wealthy is far from the truth. In the UK in 2021, over 1.5 million widows lost out on pension income after their partners died, and 59% experienced a sharp drop in income following bereavement. People who are widowed lose their partner's income. Especially if they are not married, they may not get access to their partner's pension or life insurance. Unmarried widows may also lose their home. Bereavement support payments only go to people who are married or civil partnered. Some of us, after we were widowed, did press the Fuck-It button a few times. A new car (or a car new to us). A holiday. Gorgeous boots.* Being a widow is pretty shitty, and that little fizz of dopamine is sometimes just what we need. But I think I speak for pretty much all of us when I say that we would rather live in rags and in a cardboard box with the person we loved than have all the money in the world. *Yes. That one was me. There are odd perceptions of women as widows out there. They are ancient and wizened. They are very humble. They are virtuous and will sacrifice everything. They are master criminals. They are wily husband hunters (at least where the Victorians were concerned).

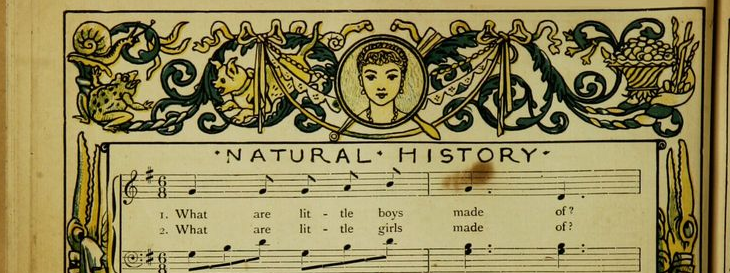

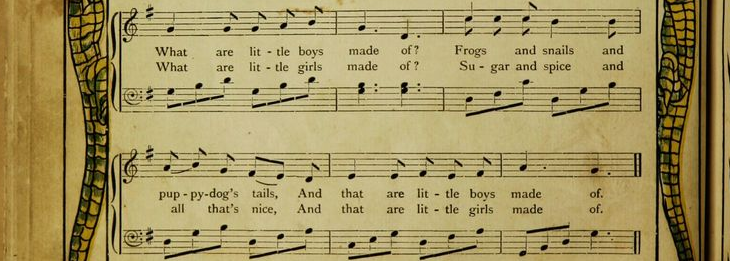

Clearly, there's not real evidence behind any of these images of widows, but the one that seems to persist is that women who are widowed are out to steal other women's partners. I've never heard of a case of this actually happening. Widows are just out to survive from day to day and they don't want anyone else's partner – they are too busy missing their own. What I have heard of, however, is women who have lost friends because the women in her friendship group are withdrawing to 'protect' their partners from the supposedly wanton widows. That way, the widow loses both female and male friends. Why? I suspect a lack of understanding about grief, and a feeling of insecurity. It's tough enough being a widow, though, without losing friends. Thank you to Dave Seed for the permission to include his picture Red Queen As widows we're not allowed to be angry by wider society. Weeping? Yes. Screaming obscenities into the void while punching things? Apparently, no. I wasn't brought up to be angry. I was brought up not to raise my voice. To be gentle and softspoken. As the memes all say, to be kind. I find raised voices uncomfortable, and I will do everything I can to avoid confrontation. This is a combination of my specific upbringing, and of growing up in a world where women are supposed to be sugar and spice and all things nice, rather than slugs and snails and puppy-dogs' tails.

But when my husband died, I was angry, in a way that I hadn't ever been angry before. Angry at him for dying and leaving me. For not having managed his diabetes better. For not having told me he was feeling ill. For dying without a will. For being on the border of being a collector and a hoarder (and it's not such a fine line) and leaving me with So Much Stuff to clear. I was angry every time I thought I was done and I unearthed another box of magazines or pile of kits or stack of paperwork and uncashed cheques. I resented him. And then I felt like I was betraying him, so I didn't feel that I could show that face of anger to anyone. I was angry at other people for having a partner during lockdown when all I had was a house of clutter and a pile of grief. I was angry because he was supposed to be my happy ever after and he wasn't. And I was angry with myself for not having seen the signs of him being ill. For not having done better. For not saving him. Showing the face of anger So many of the models of grief include a reference to anger. Anger, however, isn't something we always feel that we can show to the outside world. We may feel that people 'out there' may believe that widows whose partners have died by suicide, through violence or accident, or because of any kind of misadventure or risky behaviour, have every reason to be angry. However - I believe that all widows have the right to be angry with the situation that they are in. There are so many reasons to be angry – being left alone to cope with a difficult situation, families or in-laws that make your life hard, losing access to stepchildren, people you thought were close just disappearing, having to leave a place you adore or a job you love because it's just not tenable to stay, or simply, losing the life you thought you were going to have. Being angry at yourself, your god, the person who died, the universe. The list goes on. For someone with my upbringing, showing the face of anger was really hard. I felt like the slugs and snails were under the surface where the sugar and spice was supposed to be, and that they were going to break out and I would scream and scream and never stop. Living out in the middle of nowhere in lockdown had its bonuses. I could go and shout in a field and only the sheep heard what I said (poor sheep…) Living with the anger Its important that we acknowledge that we are allowed to be angry, and that anger is a normal human emotion. Our anger, especially when it's towards the person who died, can be tied in with unresolved hurts or resentments that can never now be sorted out. This includes anything from a silly disagreement about who should have taken the bins out, through risky behaviour that contributed towards their death, to something that comes out after death that shows they were not the person we thought they were. We can also be angry with people who have an actual or a perceived link with the death of our partner, from the drunk driver or the doctor to the person who lent them a bike on the day of the death, or delayed them so they missed the bus and had to drive to work. Bottling up anger isn't a good thing – we need to let it out – but yelling at friends and family, breaking things, hurting other people or hurting ourselves (either physically or mentally) isn't a good way to deal with it. If you feel that you are going to explode with anger:

I want to be happy for you but...

…you’re getting engaged and my fiancée died a week before our wedding. …you’re having a baby and my chance of motherhood went when my husband died just before we could start what was to be our last chance at IVF. …you’re buying a house with your boyfriend and I have to move back with my parents because my late boyfriend’s family want his flat back. We love our friends. They are amazing people (after all, we wouldn’t have them as our friends if they weren’t) and we want the best for them. But it’s really hard to see them have the things we wanted or planned before we were widowed. And it’s hard to tell them we are so happy for them when inside we are wondering why they got to have the partner, the baby, the house, the life, and we didn’t. What do to?

Widow’s fire describes the (sometimes) uncontrollable and all-consuming desire for sex following bereavement.

When we lose our partner, particularly when we lose a partner young, we lose a lot of things. And one of those is the sex life that we had with our partner, either throughout the relationship or prior to them being ill. But it’s not just about losing the sex life we had. Grief and bereavement leave us with a void, and our libido can kick in to fill that void and provide us with the kick of feel-good neurotransmitters and hormones we need. Sex is also a distraction from grief, a way to take control back in our lives, a comfort, and something that makes us feel alive. What to do when widow’s fire strikes? Masturbation releases the neurotransmitters and hormones, such as oxytocin, that make us feel good, and also helps sleep. But it’s not enough for everyone. If you want and need sex, do what you want to do, what you need to do. Just remember that you are vulnerable. Be careful. Take steps to protect yourself, sexually, physically and psychologically. Don’t be affected by other people’s opinions or judgements. And whatever you do, understand that it does not make you a bad person, or have any reflection on the relationship that you had with your partner. For some people, it’s not so much a craving for sex as a craving for intimacy. It’s the lack of touch. I remember going to a Pilates class and nearly crying when my tutor put her hand on my back to readjust the pose. I know it's not the same, but hugs from friends or family, or a good massage can help to fill the gap. Other people can shut down completely, with their bodies blocking all sexual feelings, or they can feel disgusted at the idea of sex. If you don’t feel widow’s fire, or the thought of having sex ever again turns you off, you’re not doing it wrong, because everyone grieves in a different way. |

AuthorI was widowed at 50 when Tim, who I expected would be my happy-ever-after following a marriage break-up, died suddenly from heart failure linked to his type 2 diabetes. Though we'd known each other since our early 20s, we'd been married less than ten years. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed