|

My day job is writing about science and medicine, and over the past decades I have read hundreds, if not thousands, of scientific papers. They rarely start with a Shakespeare quote and a discussion of poetry and fiction. The text above is taken from a 1986 letter to the British Medical Journal by Dr Brian McAvoy, then a senior lecturer at the University of Leicester.

The letter, called Death After Bereavement, talks about the increased risk of death after losing a partner, with a higher risk for men, and for people who are bereaved young. Dr McAvoy found the risk to be higher in the first six months for women, and in the second year for men. This increased risk of death has become known as the widowhood effect, and has been confirmed in other studies and in meta-analyses (scientific papers that combine the results from a number of previous studies). A study from March 2023, in people over 65, showed that the risk of death was highest in the first year after bereavement, and higher in men than women. Overall, the risk of death was 70% higher for men aged 65–69 years, and stayed higher for six years. For women in the same age group, the risk was 27% higher in the first year. Widowhood effect causes of death include cancer, cardiovascular disease, infections, accidents and suicide. Why does this happen? It’s not clear why the widowhood effect happens, or why the impact is greater in men. There are a number of potential reasons:

What to do Self-care is important after bereavement, and it’s more than just a bubble bath. It’s about getting sleep, eating as well as you can, keeping in touch with people, and seeking medical care when you need it. Psychotherapy and counselling can also really help if you are struggling.

0 Comments

Warning – contains swearing

Gluttony, often mistaken for greed (part 1 and part 2), is an excess in eating or drinking (hunting for definitions brought me to crapulous, a brilliant word). Being bereaved is rough, and sometimes we need that extra bit of comfort. I know that I took to comfort eating, comfort drinking and comfort shopping as coping mechanisms when Tim died. This piece isn't about shaming or guilting people for their choices. Being bereaved is hard enough, without a blogger telling you what to do. It's just here if this is something that you are thinking you want to consider, or to change. Comfort eating, emotional eating or stress eating Food is my go to when I'm grieving, depressed or stressed. And it's generally not classy food – it's cheese straight out of the fridge, toffee popcorn in handfuls, or crisps in huge bags. In these situations, I also don't really notice what I'm eating, I just notice when I reach for the next handful and it's gone. I have ADHD, and impulse control is not one of my strong points – if I see food in the cupboard, I want it and I don't want to wait. Comfort eating when we are low feels like a form of self-care, because it triggers the reward systems in our brains, and makes us feel better, at least for a moment. And in the early days of grief, when I had no appetite at all, getting calories in any form was a good thing. Not eating properly, if it lasts long term, can have an impact on our mental and physical health. Guilt, shame and regret can be part of our feelings of grief anyway, and if we are feeling guilty about what we eat, that could just pile on top. If you want to make a change Cooking and eating after loss is hard, whether it's the challenge of cooking for one rather than two, the additional costs of food shopping for one rather than buying in bulk, or simply a loss of appetite or missing what used to be a shared pleasure. Meal kits for one, or even just a new cookery book can help with getting back into the habit of cooking, and batch cooking helps to fill the freezer for those days that you just can't face the chopping board. Signing up for a healthy eating and exercise program (I'm using the Glean App) is helping me to structure my eating and encouraging me to exercise, and the peer support works to keep me on track. But it's whatever works for you and makes you feel better. Emotional drinking A glass of wine, a gin and tonic or a really good single malt is my treat to myself, and I love how it tastes and how it makes me feel. There were times after Tim died, or when I've been coping with depression, that I drank a lot to relax, to numb how I felt, or to be able to fall asleep. Like comfort food, alcohol releases the feel-good chemicals in our brains. It calms anxiety and slows down overthinking. It takes the edge off. But too much of a good thing isn't always a good thing, and too much alcohol impairs judgement, and can cause health problems and problems at work or with friends and family. If you want to make a change If you want to reduce what you drink, there are apps to help you work out how much you actually drink, and help you cut down or stop drinking, such as Try Dry from Alcohol Change UK, MyDrinkaware, or the Drink Free Days app from the NHS. Some people find reducing what they drink is too hard and it's simpler to stop drinking altogether, and apps like these can help too. If you feel that you are dependent on alcohol, or that alcohol is harming you, talk to your GP or contact an organisation like UK SMART Recovery, Alcohol Change UK or FRANK. Comfort shopping or retail therapy I've talked to other widows about 'pressing the fuck-it button', which describes moments of retail therapy that make us feel good, from gorgeous boots during lockdown when there was nowhere to go (yes, that was me), to a new car or campervan. You can even buy the button. Buying things can help us to reclaim what were shared spaces as our own. Tim died next to me in bed, so one of my first purchases was a new bed and new bedding. But retail therapy can also leave us with a stack of things we will never use or wear. Being widowed can leave people with a reduced income, or push them into poverty, and when emotional spending gets to be too regular, it can make a huge economic impact. If you want to make a change Monitoring spending highlights how much often we are splashing the cash. Taking shopping apps off your phone, delaying purchases by 48 hours to give you thinking time, and sticking to a budget so that you can shop, just not too much, can slow the spending down. Another option is to pledge to buy only second hand, and to sell what you aren't using, either to put in your slush fund or to raise money for charity. 'Self-care' is a bit of a buzzword. It's become about 'me time', bath bombs, scented candles, manicures, facemasks, herbal teas, touching trees and drinking a lot of water out of an enormous plastic water bottle. While none of these are wrong in themselves, they offer a fleeting moment of care, and may not appeal to everyone. They can also become a pressure, leaving grieving people feeling worse when the solutions don't make everything better.

In grief, self-care is actually about caring for our mental and physical health and keeping ourselves safe and well. Caring for ourselves The most important part of self-care, which sounds easy but is actually quite hard, is being kind to ourselves. It's about being as good to ourselves as we would be to others in the same situation, giving ourselves permission to feel sad, to say no, to take breaks and to get things wrong sometimes. Remember, we are doing our best in a situation not of our choosing. Self-care can include:

Meditation and mindfulness may help. However, as someone with ADHD, these allowed too much space for intrusive thoughts; it was too much for me but some people find it very useful. There isn't much information on the issues associated with the combination of grief and the menopause. So this is going to be rather shorter than I hoped it would be. The symptoms of the menopause, such as lack of sleep, loss of self-confidence, low mood, anxiety, brain fog, weight changes, emotional overload, exhaustion and flare ups in other health conditions, can overlap with many of the experiences in grief and blur in together. This can make it harder to work out what is grief and what is the menopause and makes both feel worse. The stress associated with grief may also worsen menopause symptoms, and there is a possibility that stress could even bring on an earlier menopause. There can be grief associated with the menopause itself, which could complicate the grief of bereavement. Menopause can bring up thoughts of the loss of youth and of aging, which may trigger grief about the loss of a partner.

For people who are grieving, the menopause can highlight the secondary loss of the chance of conceiving and carrying a baby. This can be especially hard for those who were trying for children at the time of their partner's death. The menopause also comes at a time where people may be caring for aging parents, or grieving their loss and missing their support. The fact that the symptoms of perimenopause and menopause and the symptoms of grief are so hard to separate may also mean that women (and trans and non-binary people) don't seek help for menopausal symptoms at what is already a difficult and overwhelming time. Coping with grief and the menopause Like grief, there is no one solution to the menopause. Be aware that the menopause may be masking or adding to your grief symptoms and be gentle with yourself. If you are struggling with the menopause talk to your doctor – there are options that can help you deal with the physical and psychological symptoms. Grief is bad enough without the menopause making it worse. HRT can help with some symptoms (I have just started with HRT patches to see if they can help with my fluctuating body temperature and disturbed sleep). The Menopause Charity's website has information, news and expert advice, and the NHS website has a section on 'Things you can do'. When Tim died it hurt. And I don't just mean that my heart broke. I mean that I hurt physically. I felt so tired that my bones ached. My stomach hurt. I felt sick. My head ached. I didn't experience this, but I know that other widows had chest pains so bad they ended up in A&E. And there's widow brain too. It's all completely normal with the shock and sadness that comes along with bereavement.

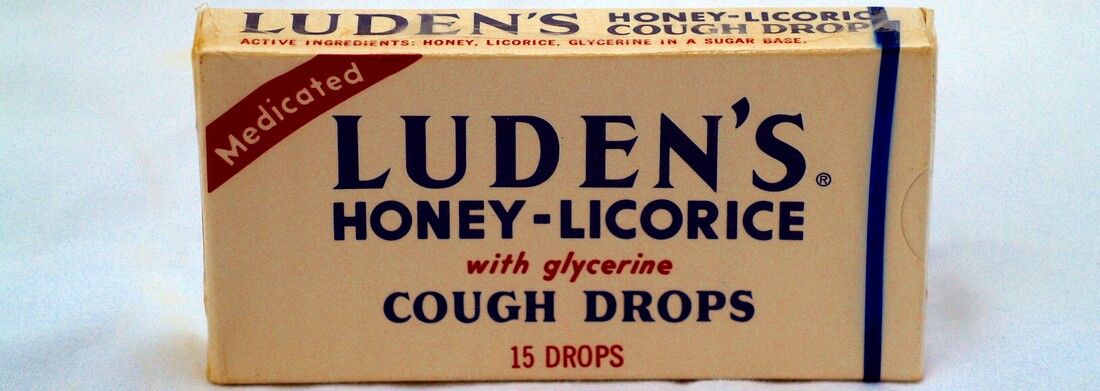

Please remember, though – if any of these symptoms become distressing, last a long time or get worse, please talk to your doctor, call 111, or in an emergency, call 999. Being exhausted Grief messes with our sleep, gives our brains a lot to do, stops us eating properly – it's hardly surprising it leaves us exhausted. Try to eat as well as you can, sleep when you can and manage your energy. Feeling pain in muscles and joints The tension of grief can leave us with aches and pains, and grief can actually make pain worse. Try to exercise if you can – even just a walk round the block – as exercise can improve mood. Try having a massage, which can also help skin hunger. Colleges that run health and beauty courses often have low-cost massages to provide experience for students. Chest pain and shortness of breath Chest pain and shortness of breath are associated with anxiety. However, if these come on suddenly or are painful, talk to your doctor of call 999 – paramedics and doctors would rather be called in for something that isn't serious that miss something that really is. Headaches Headaches often accompany anxiety and stress. Trying to relax can help, but it's easier said that done. Warm baths and music helped me. Widow brain The confusion, forgetfulness and lack of concentration that comes alongside bereavement is often known as widow brain. Stomach upsets and appetite changes Grief can make us eat more, eat less, eat junk food, comfort eat feel sick, feel hungry, think we are never going to feel hungry again. This is all normal and will settle. Try and eat some fruit and veg, but eat what makes you feel comforted. Picking up bugs Grief can affect our immune systems, leaving us more vulnerable to infection. Wash your hands regularly, make sure kitchen surfaces are clean, cook food thoroughly, get the vaccines you are offered, and wear a mask in crowded palaces during cold and flu season can help to keep infection levels down. Health anxiety One of the issues with the physical symptoms around grief is that they can become part of health anxiety, where we become convinced that every symptom, from a headache to a painful toe, is something life-changing. I have gastritis, and sometimes when its bad I vomit. I threw up blood one day. My wonderful GP, who was an incredible support to me after Tim died, fast-tracked me for an endoscopy while reassuring me that she was sure everything was okay, and fortunately she was right. On the flip side, bereavement can also leave us caring less about our health and ignoring symptoms. If you are on regular medications, keep taking them (pill boxes and reminders on phones are really helpful) and build in a bit of self care. Posting on the blog has been a bit patchy over the last couple of weeks as I've had a cold. The kind that makes your throat sore and scratchy, your nose both run and block up, and your voice swoop between a squeak and a croak. And it's reminded me how hard it is being ill on your own.

Winter can be hard for people who are widowed. It's dark and cold, and it’s the time when we are most likely to get colds and flu. Getting ill also reminds us that we are alone – there's no-one to bring that cup of tea, check in on us, get us something to eat or pass us some paracetamol. There are a few things we can do, though, to make things not seem so bad.

When we lose someone that we are close to, it of course leaves us grieving. It can also remind us of our own health and mortality. This can turn into health anxiety, which is worrying too much about whether you are seriously ill or are going to become seriously ill. It can affect your day-to-day life. I don't have health anxiety for myself, but I do worry about other people. I've always catastrophised when someone doesn't answer the phone, or is late, or has a symptom, but it's got worse since Tim's sudden death. Early one morning my current partner fell down the stairs. I got her to her feet, and she fainted, slithered through my arms and slumped against the wall. She started making guttural noises, much like Tim did just as his heart stopped. I was shouting at her but couldn't rouse her. I was convinced that she was going to die, and I was mentally rehearsing the 999 call and CPR. Before I could get to my phone, she came round with no awareness that she had passed out, and no aftereffects other than a painful ankle. Once I knew that she was okay, I did the only rational thing and burst into tears. The incident left me with flashbacks for a couple of days. Dealing with health anxiety

Look after yourself Bereavement can also make us care less about our own health, and stop looking after ourselves. This is your reminder that you matter, you are important, and that you need to be kind to yourself and take care of yourself. If you are worried that you are ill, call 111 or talk to your doctor. |

AuthorI was widowed at 50 when Tim, who I expected would be my happy-ever-after following a marriage break-up, died suddenly from heart failure linked to his type 2 diabetes. Though we'd known each other since our early 20s, we'd been married less than ten years. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed