The darkness of winter is tough, especially for widows living alone. Here are a few hints and tips for making the winter feel more comfortable.

Someone once said to me to think of this time of year being when the seeds are in the ground waiting for spring. This helps me feel a bit more positive about the dark mornings. Seasonal affective disorder Many people get affected by changes in the seasons, but if the winter blues are lasting a long time and really affecting your life, you might have winter seasonal affective disorder (SAD). This is a low mood that gets worse in the winter. According to the NHS, symptoms of SAD (sometimes called winter depression) include:

Our sleep patterns, appetite, mood and activity are linked to levels of light, and for some people the levels of light in the winter just aren't enough. Lower levels of light can also affect our sleep-wake cycles. There a few things that might help:

Vitamin D may or may not help SAD, but the NHS recommends that people in the UK should consider taking a daily vitamin D supplement during the autumn and winter. If SAD is really affecting your life, talk to your GP. For some people, cognitive behavioural therapy, counselling, psychotherapy or antidepressants can help.

0 Comments

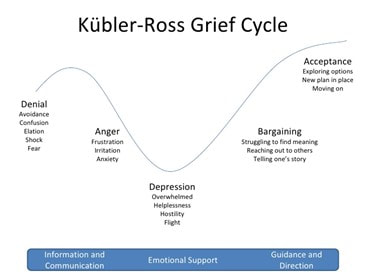

This is the model that a lot of people pull out – that grief has five stages, and these are denial, anger, depression, bargaining and acceptance. And yes, I've gone through all of these. Denying that it can be real. He was alive last night and he's dead this morning. Fury at him and at the universe that he's gone. Feeling so low that I couldn't believe I could fall lower. Bargaining with the universe to find a reason why it happened to him, and not to the awful people in the world. And acceptance that this is the world I now live in. I didn’t go through them in any order, and I cycled between them, across them and around them. My grief was more like this: The reason that this model doesn't really work for bereavement is that it wasn't actually intended to be about the grief of losing someone we love. Swiss-American psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross' created the model to help terminally ill people to come to term with their own illness and death. David Kessler, her co-author, has worked with her to create models for people who are grieving. He says that there is no typical loss, and not everyone goes through all of the stages, or in any particular order.

Theresa Rando's model of mourning breaks the process into six parts, within three phases, and these are part of the process of moving through grief. Each begins with the letter R. To a certain degree, these overlap with Worden's four tasks.

Avoidance phase In early grief we struggle to understand what has happened, and accept it as real. We avoid the reality. In this model we need to recognise what has happened to us. 1. Recognise the loss This is the step of acknowledging and understanding the death, and accepting its reality. This also includes understanding the cause of the loss, which can be difficult for people whose partners were killed in accidents, were murdered, or died by suicide. Confrontation phase In the confrontation phase we process what we are going through. 2. React to the separation This step is about feeling all the emotions that are part of grief and loss – anger, pain, sadness, sorrow, and all the other things we go through – and accepting them. Reacting to them. Working through them. Sometimes we might have to give yourself permission to feel all of these things. It's also about accepting the secondary losses – things like the future we planned, the places we were going to go, the growing old together we had expected. 3. Recollect and re-experience the person and the relationship When things begin to feel less raw, we can begin to remember the people we lost. It took a while after Tim died for me to even think about the things we'd done together, the things we'd loved doing together. 4. Relinquish attachments to the old life This sounds harsh but I don't think it's meant to be. It's not about moving on or forgetting or leaving behind. It's about working through what has happened, and about accepting how it has changed our past, our present and our future. Accommodation phase The accomodation phase is about creating a new meaning and a new life, without forgetting the old. 5. Readjust and move into the new world The readjustment stage talks about accepting who we are now and making a new identity for ourselves, while we still remember the person we lost. 6. Reinvest The first big decision I made after Tim died was to do a part-time MA. For me this was reinvesting in myself, and in a future that I hadn't expected or planned for but that I wanted to try. In his book Grief Counseling and Grief Therapy, William Worden suggested that there are four tasks of mourning that must be carried out for "the process of mourning to be completed" and life to get back on balance. While I like aspects of this model, I disagree that we ever complete the process of mourning, and the idea of tasks to be ticked off feels like a lot of additional pressure.

The tasks are: 1. Accept the reality of the loss Death, especially a sudden death, leaves us reeling. We can't believe that they are gone. Accepting the reality isn't just knowing the truth of the bereavement, it's understanding that everything has changed. For me, the funeral was an important part of this. 2. Work through the pain of grief Grief is different for everyone. We move from a raw, savage pain to a deeper, more visceral grief, which then shifts to something we can survive with. The time this takes is also different for everyone – weeks, months, even years. A wonderful friend of mine talks about 'sitting in' the waves of grief and letting them wash over you – this helped me to process the pain. 3. Adjust to an environment where the person is missing For some time after Tim died, I would turn around and expect to see him, especially when the door downstairs made a characteristic little rattle. Adjusting to the environment where they are not here isn't just missing their physical presence. It's missing their role in your life. Losing a partner, particularly losing a partner young, takes away the past we shared with them, the present we shared with them, and the future we hoped to share with them. 4. Find an enduring connection with the person who has gone while embarking on a new life However much our lives change post loss, we keep the people we lose as part of us. This is why I don't talk about moving on, I talk about moving forward (and this amazing talk by Laura McInerny explains more). Keeping a connection with Tim includes talking about him, having his photo up, and raising a glass to him on his birthday, our wedding anniversary and the anniversary of the day he died. In 1996, New Zealand-based grief counsellor Lois Tonkin came up with the model of growing around grief. The idea is that in the early days, grief consumes us totally. It fills up all of us, awake and asleep. I knew – or hoped anyway, that things would change. I thought that I would stay the same size and my grief would get smaller. Over time I realised that my grief actually stayed the same size. But as this model showed me, my life got bigger around it. My grief is still there, and always will be, but I have changed and grown.

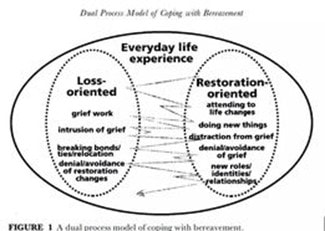

The dual process model, developed by Margaret Stroebe and Henk Schut, suggests that we move back and forth between two modes as we grieve.

When I was in the loss-oriented mode, grief was the main thing I felt. I felt sad, lonely and angry. I couldn't believe that I was going through this, and I couldn't understand why. As a freelancer, I needed to go back to work as otherwise I had no income. And when I was working I felt almost normal. I was restoration-oriented. It distracted me from the awfulness. And then I felt bad that I wasn't grieving. I was coping. This model helped me see that my mind was taking me away from the grief sometimes, particularly when it got too overwhelming, and it was helping me to look after myself.  In my early days of grief, everything was a blur and nothing seemed real. I had incredible amounts of support from my parents-in-law, my family and my friends, but there was still a tremendous amount to do – arranging the funeral, and doing the 'death paperwork', with everything from closing bank accounts to cancelling the dentist. And then I started to wonder, or even worry, that I wasn't grieving properly. I was grieving too much. Or too little. I was coping too well. Or I wasn't coping well enough. Reaching out to the wonderful people at Widowed and Young made me understand that there's no right way to grieve. And generally, there's no wrong way to grieve either. The way that you are grieving – that's the right way to grieve. Grieving lasts as long as it lasts, and in some ways it lasts for always, as we don't want to forget the people that we loved, and still love. But it does change. It gets less raw. And we learn to live alongside our grief. People have developed many models of grief to try to understand what we go through when we lose someone, and what can help us. I have written blog posts about a number of different models. The dual process model and growing around grief are the ones that helped me most, but it's important to remember that these are just models, and not rules, and different models can help different people. Having said that there is no wrong way to grieve, and no set time that grieving lasts, a small group of bereaved people develop what's called complicated grief disorder. This includes exaggerated grief symptoms over a long period, sometimes years or decades, and a feeling of being trapped in grief. Complicated grief overlaps with depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. Talking to a psychotherapist might help – it certainly helped me when I had signs of PTSD after Tim's sudden death. Christmas can be such an emotional time, but it can be even more challenging for widows, because it brings up a lot of memories, happy or sad. As with so many things about being a widow, there is no right or wrong. No rules. Do what you need to do. And do it as one moment, one step, one breath at a time.

Avoid the hype Christmas is everywhere, and you can cut down your exposure to it by using ad blockers online, unsubscribing from marketing emails, watching DVDs, streaming services or BBC to avoid ads, listening to albums, podcasts, spoken word radio such as Radio 4, Radio 4 Extra or Radio 5 Live or music streaming services to avoid Christmas music on the radio, or recording live TV so you can fast-forward through ads. Shop online (at independent shops if possible) to avoid Christmas fluff, furbelows, jumpers, tinsel and endlessly looping Christmas music. Taking the last couple of days off work before Christmas can get you out of all the Christmas talk. Give yourself permission Give yourself permission to laugh, cry, go out, stay in, or go to things and leave early. And whatever you plan to do, you are totally allowed to change your mind. Say no Don't do anything you don't want to. Fib if you need to, but just say no. You don't have to go to the party, wear the jumper, or get involved in the Secreat Santa if you don't want to. Announce your intentions early The first year I decided to spend Christmas afternoon with friends. The second, I decided to head off to a shepherd's hut in the Lake District. Both years I told my family early, to stop the well-intentioned invitations. I love my family, and I love spending time with them, but I just didn't want to be part of a family Christmas without Tim. Be aware that things can get overwhelming If you are part of a big celebration, it can get too much sometimes. Take a breath, try grounding (five things you see, four things you hear, three things you touch, two things you smell, one thing you taste), or find a quiet corner for a moment. Prepare people Let people know that you might have tough moments, and let them know whether you want to be fussed, ignored, hugged or distracted. And if you are spending it alone, you can ask someone to check in on you at some point of the day if that would help. Have an exit strategy If I go to a big event, I like to arrive early so that I can find places to hide if I need them, and so that I'm not walking into a full and busy room. Driving or having a taxi booked means that you can leave early if you want to – taxis can always be rescheduled if you find you are having fun. Ignore Christmas completely It's allowed. Buy nice non-Christmas food, stock up on non-Christmas films, binge on box sets. Shut the door on Christmas Eve and ignore the world, and then emerge on Boxing Day. Switching off social media can help you to keep Christmas away too. Don't give in to pressure from others Spending Christmas alone, with friends, with strangers, working, volunteering, whatever – if it's what you want to do, then just do it. Don't feel that you have to fit in. Volunteer Volunteer if you want to, bit don't do it because you feel you ought to. Create new memories Do something totally different. I have amazing memories of the year I went and stayed in a shepherd's hut. I stocked up on goodies, stacked my Kindle full of books, saw a friend for Christmas lunch, but for the rest of the time I looked at the view, pottered around, ate my body weight in chocolate, and slept. You can have a tradition of not having a tradition. Buy yourself something nice A big present, a little present – it doesn't matter what it is, but have something special just for you on Christmas Day. You can say it's from you, or from your partner, or from your cat. Whatever you want. Enjoy it You are allowed to enjoy whatever it is that you are doing. Don't feel guilty. Make plans It might be a good idea to have some plans made, otherwise you might just drift and feel worse. But don't plan so much that you feel guilty about not doing it all. Stock up on the food you need, decorate the house and tree if you want to, plan to catch up on some hobbies or some reading, go for a walk, pamper yourself with a long bath. Whatever you really fancy that you don't normally have time to do. |

AuthorI was widowed at 50 when Tim, who I expected would be my happy-ever-after following a marriage break-up, died suddenly from heart failure linked to his type 2 diabetes. Though we'd known each other since our early 20s, we'd been married less than ten years. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed