|

When I stepped out of the door the morning that Tim died, I couldn’t believe that village life could go on as normal when my life had so suddenly and drastically changed. But it did.

Over the years since 2018, I have rebuilt my life, embracing my sexuality, going back to university, meeting and marrying my wonderful Dee, and making a fresh start in a new location. All of these changes have left me sometimes feeling that I'm living two parallel lives. There's the life that I live now and the other that carried on, where I am still married to Tim. We still live above the bookshop. And he is pricing books downstairs. The life we live without them can leave us feeling guilty and resentful. About the what-ifs, the things we did or didn’t say, simply that we survived. And for going on without them. Going to work. Seeing friends and family. Making changes to the house. Enjoying ourselves. Doing things that they will never do, in places that they will never see, and making decisions that they will never know. There’s nothing I can say that makes this better. As Tim would say, it is what it is. We continue without them, moving forward but not moving on. And as a community, we do it together.

0 Comments

So many of us have social media accounts, from Facebook and X/Twitter, through WhatsApp, Instagram and TikTok, to Snapchat, Pinterest and LinkedIn (and so many more). This digital footprint will live long after we do. Some companies will automatically delete accounts after a certain length of time. Others allow you to make decisions, including deletion and deactivation; these options vary between providers. Deactivating can hide the profile until you decide what to do with it.

Keeping accounts open Social media can be a good way to tell people about a death, but it’s important to tell family and friends first. Keeping accounts open also lets you tell people about any arrangements, allows you to access their photos, videos and posts, and means that family and friends can make posts in memory of them and stay together as a community. However, because other people can post on an open account, this can mean that you see things that may upset you. Memorialising accounts Memorialised accounts allow people to have a place to remember someone and to read that person’s old posts. The account will make it clear that the person has died, and will no longer send notifications. Deleting accounts Deleting an account protects you from seeing things on their account that might upset you, but deletion is permanent. Different companies will need different things to close accounts. These are likely to include their full name, their profile name, ID or link, their death certificate, and proof of your relationship with them. Creating a digital will If you have strong feelings about what will happen to your digital footprint after you die, you need to make plans by creating a digital will. This can include IDs and profile names, and requests to delete or memorialise accounts. Living with grief can be truly exhausting, and leaves us with the feeling that we cannot achieve anything. So, today, celebrate all of the little wins, from cleaning your teeth to changing the sheets, and from feeding the cat to cooking a meal for yourself.

Tomorrow is the sixth anniversary of Tim’s sudden and unexpected death. For each milestone date I’ve found the run up to be much harder than the day itself, and I expect this year to be the same. What has changed is the length of the run-up.

In the first few years it began on my birthday, which was also our wedding anniversary, in September. It continued through his birthday in December, Christmas, New Year and then to his death in February. Now, I can raise a glass and remember him on those dates, and the run up period doesn’t begin for me until February. In the early days of grief, it surrounds us, and its rawness is part of our every waking moment. Over time, in my experience, grief softens and becomes less raw, and while it remains the same size and stays with us always, our lives grow around it. The first feeling I had when Tim died was numbness. His death came out of nowhere, and I went into shock. I felt like I was separate from everything, and was watching myself and the world around me from a great height. This is known as dissociation. I also shut down – I didn’t only not feel grief, I didn’t feel anything at all. Both of these are totally normal responses to trauma, particularly in the early days.

Later on, there were times where I worried that I was coping too well. I wasn’t sobbing all the time. I was working and coping. And feeling guilty because I was working and coping. Someone told me about the dual process model, where grieving people switch between modes of coping and grieving. I thought of it as my mind protecting me from grief some of the time. The feeling of numbness can last, and this may leave grievers feeling that they aren’t grieving ‘properly’. It can just be a different way of grieving – not everyone grieves publicly, and all experiences of grief are different. However, if how you are feeling is affecting how you live your life, find someone to talk to – a friend, family member, support group, doctor, counsellor or psychotherapist. Valentine’s Day is coming up. As a day focused on romantic love, it’s a tough one for many widows, and like all milestones, the first can be the hardest. Also, like other milestones, the run up to it may be harder than the day itself

What to do on the day

Some online marketing companies offer the opportunity to opt out from Valentine’s Day messaging (this can also be an opportunity to unsubscribe from all the marketing emails that are cluttering your inbox). And if it helps – Valentine’s Day has a pretty dark origin story. Alternatives to Valentine’s Day

There’s no timetable or no ‘normal’ for grief – I believe that grief lasts a lifetime, that it’s different for everyone, that it changes over the days, months and years, and that we grow around it. People who are grieving can describe themselves as feeling ‘stuck’ in grief, where nothing seems to change, and it doesn’t feel like it’s going to get any better. I struggled with this around six months after Tim died, when the numbness wore off and the reality kicked in.

There are a number of things that can make the feeling of being stuck more likely:

What can help I found that making ‘done’ lists rather than ‘to do’ lists helped when I felt stuck. These were anything I’d achieved, from getting up and cleaning my teeth, to making myself a meal or doing the sadmin. Looking back through these showed me how I was actually moving forward. Keeping a journal or diary can help too. Talking to people who understand is a major help. People who have been bereaved can be a listening ear, tell you whether what you are going through is normal (though there is no real normal in grief), and offer suggestions of what has helped them. Joining a local or national grief organisation will provide you with a support network. However, don’t compare or judge your grief against other people’s. Everyone’s grief journey is different, and there really are no Top Trumps in grief. Take time to grieve. Sometimes you just have to sit out the waves of grief and let them pass. And remember that self-care is a big thing – looking after your mind and body is very important while you are grieving. When feeling stuck sticks around For a small proportion of people, however, grief does become something more. Prolonged grief disorder, while a controversial diagnosis for some, describes a grief that is persistent, enduring and disabling, or that gets worse. This might mean that even after time has passed:

While these are all symptoms of raw grief, there may be a problem if you experience them at an unchanged level over a long period, or if they get worse. If your grief significantly affects your ability to function on a day to day basis for a very long time after your loss, if it makes you isolate yourself from others, or you feel that life is not worth living, find someone to talk to – this might be your GP, a counsellor or a psychotherapist. Moving into a new year for new widows means moving from 'My partner died this year' to 'My partner died last year'. For those who have been widowed longer, it can feel like their person is moving further into the past.

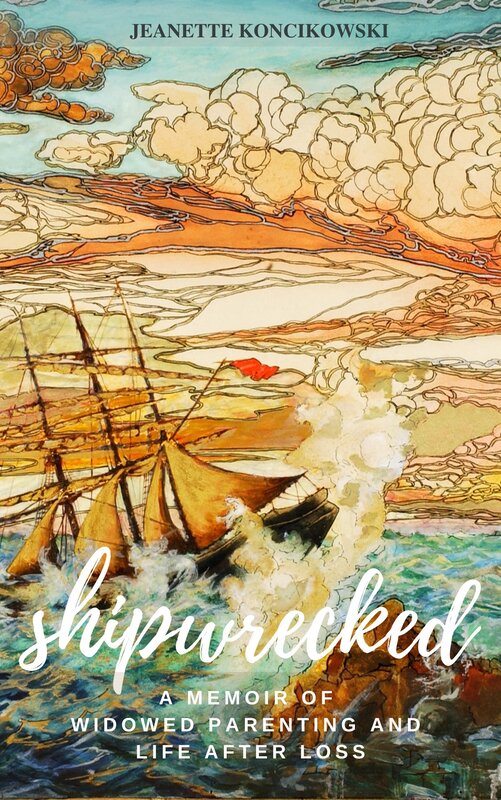

Another unexpected loss. This is a guest post from Jeanette Koncikowski. Jeanette is the founder of the Widowed Parent Project. You can follow her on Twitter/X @widowedpp.

I kept secrets for the 21 years of my relationship with my husband. Hell, I kept secrets for most of my life. This is the way trauma (and trauma bonds) work. The secrets existed to protect the people I loved from the truth. From the deep pain I held that I wanted to prevent them from sharing in. I thought I could love beyond truth. I believed that love would save us. And it has. Just not at the expense of truth. When 2024 comes roaring in at midnight on New Year’s Eve, I will be entering a full decade of life since losing my first husband, Mark. We were 36 years old when he died suddenly. His death was the answer to how our marital separation would end. Throughout our separation, I had maintained to him that our marriage would now be based on conditions but that my love for him was unconditional. Mark was my highschool sweetheart. He was my first love, my protector, and my rescuer. The father of my two children. From the start until the end, our 21-year relationship was nothing if not intense. He loved me fiercely. But he could not give that same love to himself. Most people that came to Mark’s memorial service did not know we had been separated. Some knew of his physical health struggles with epilepsy. A few closest to us knew he had been “touched” by depression (as if depression were a dove landing on your shoulder and not the god-awful thing that could turn him from Jekyll to Hyde.) Only a handful of his friends who he partied with knew of his substance use. But no one lived with or loved him through these difficult things the way I did. Mark’s death was also not the first significant loss I had in my late thirties. In the four years before his death, I had lost a pregnancy in my second term and I watched my mother suffer from terminal breast cancer until she died at the age of 62. One of my closest friends died suddenly the following summer and it was her death that was the catalyst for me to walk away from my crumbling marriage. My grandmother died next and thirteen months into our separation, when Mark and I were actually, finally, in the process of deep healing, I lost him too. Mark died alone in the middle of the night in a run-down apartment building, just a few blocks from where our children and I lay sleeping in the home we used to all share. I was the one who found him in the morning. His life was more than his illnesses. He was a loving father, a caring chiropractor, and a good friend. I blamed myself for his death. I thought if I had just been there, I could have somehow intervened and rescued him, as I had done so many times before, when death seemed to have him in her reach. Going through loss after loss, culminating with Mark’s death, gave me the gift of rawness in grief. What does life mean when the people you love most can die on you at any time? When they can die on you in quick succession? It was leaning into this vulnerability that finally stripped away my ego, which had been the part of me carrying all of the secrets of our past and present. I realized that they were not, in fact, protecting anyone. I did not have that kind of power or control. When we show up in our grief the way we really are: messy, devastated, guilt-ridden, shame-ridden, blaming ourselves, hating ourselves...when we let ourselves feel these hard feelings, we can eventually accept that none of it was our fault (nor the fault of our deceased loved ones). Facing the guilt and fears I had about what Mark’s final moments were like allowed me to also face the good, the bad, and the ugly in our relationship as a whole. It was then that I began to heal. The funny thing about healing from trauma is that it’s not a “one and done” kind of thing. Opening the wounds from Mark’s death opened the wounds from our marriage which opened the wounds from my childhood. Trauma therapy taught me that once I started showing up as my true self in my grief, I could make space to show up as my true self in the other areas of my life. Learning to be more authentic required me to also have and keep boundaries in relationships. I learned how to walk more humbly and share more of my real thoughts and feelings with the world (and most importantly, with my children and my next partner). I learned that asking for help when we struggle is not a sign of weakness but of strength. It was not a linear walk. Mark had kept secrets from me too and some of those had trickled down to the truths our children carried. I learned how to replace secrets, shame, and guilt with grace: for myself, for Mark, and for everyone I loved. What I have ultimately learned in the years since Mark died is the embodiment of one of my favorite quotes from Brene Brown. “Owning our stories and loving ourselves through that process is one of the bravest things we will ever do.” Whatever your loss and love story, know that it mattered. It is valid. That your grief, however complicated, also matters. And you are not alone. Being honest about who you are, what happened to you, and what you need now will help you cultivate a life not only of authenticity but of joy. Life may teach us to hide the darker parts of ourselves from others but death teaches us too. It shines a light in the holes of our heart. If we follow that light, we might just find the path back to our true selves. ____________________________ Jeanette's first book, Shipwrecked: A Memoir on Widowed Parenting and Life After Loss, will be released in Spring 2024. Sign up for launch news or learn more about grief coaching with her by visiting Thrive Community Consulting LLC. After Tim died, and after the numbness worse off, I felt that I had to live my life to the full because he wasn’t here anymore. It’s made me realise that life is short, and I’ve taken opportunities, tried things that I might not have done otherwise, and put myself well outside of my comfort zone. And I’ve loved some of them, liked most of them, and found a few I’d rather never touch again with a very long bargepole.

However, this can mean we put ourselves under too much pressure to do things ‘for’ our person, and if it doesn’t work out, we feel guilty or a failure. Grieving can involve these feelings already, and we don’t need more of them. I’m still aiming to live my life to the full, but now I’m doing it for me. Because life is too short. |

AuthorI was widowed at 50 when Tim, who I expected would be my happy-ever-after following a marriage break-up, died suddenly from heart failure linked to his type 2 diabetes. Though we'd known each other since our early 20s, we'd been married less than ten years. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed